Art & Artists

Ester Partegàs Explores the Contradictions of Motherhood

By Emma McAleavyOctober 6, 2020

Photo by Ester Partegàs

Ester Partegàs was already thinking through themes of motherhood and domesticity when the COVID-19 pandemic sent her family into quarantine in their home in Marfa, Texas.

Ordinarily, Partegàs spends most of the year in New York City where she shares a small one-bedroom apartment with her husband and her five-year-old daughter. Marfa is where the family usually spends the summer months. But, with her daughter’s school and both her and her husband’s teaching jobs moving online, the family opted to return in mid-March.

“I almost feel guilty saying it, but I’ve been very well,” Partegàs said when I reached her over the phone in late May. “Having this house literally in the middle of nowhere is a privilege.”

Partegàs is a sculpture artist whose work deals with ordinary, often disposable objects. Trash, old tarps and containers have been the protagonists of her work. “I feel that they know a lot about us,” Partegàs says of these kinds of objects, “But they are scorned. They are not considered worthy.”

Photo by Ester Partegàs

Partegàs’s most recent work, “Baskets. No retention” features large scale replicas of broken plastic laundry baskets made from cardboard, cotton fabric, wood glue, acrylic and enamel paint sealer. The work considers the paradoxes inherent to the domestic object; “care implies repair, security assumes precariousness, construction announces destruction.”

Partegàs has been contemplating these kinds of domestic paradoxes for years.

Like many mothers, Partegàs found the transition to parenthood challenging. The task of juggling motherhood, teaching commitments, and a flourishing career as a sculpture artist brought her to a point of crisis. It wasn’t sustainable, she said. “I assumed my art and my family were two separate things. I was trying to keep my art practice as it had been.”

But keeping her work and her family separate wasn’t working for her. So, little by little, she began paying attention to what was happening in her family in the same way that she would pay attention to what interested her in her work. The result was a slow merging of the two realms of family-life and art.

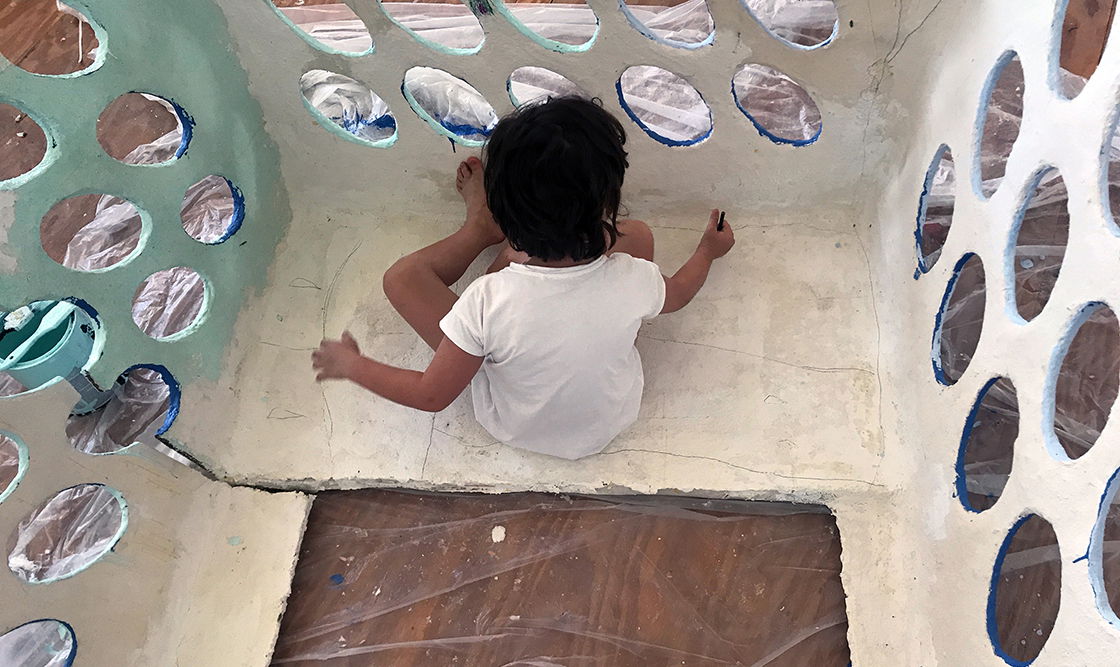

That merging reached its apex during the months of sheltering in place in Marfa. Since her daughter is too young to be left along in the house, Partegàs began bringing her in to her art studio, allowing her to play with and even contribute to the sculptures. It was the only way she could continue working. “In a way, she mimics what I do but she does her own thing,” Partegàs said of her daughter, “She wants to play all the time, so my sculptures cannot be precious.”

Photo by Ester Partegàs

Partegàs’s second iteration of her basket sculptures includes some of her daughter’s drawings on the inside of the baskets, in an interior space meant to invoke a child’s room and a playful space. The exterior of the basket, meanwhile, draws on the idea of a DIY trap one might use to catch a rabbit or a fox in the woods.

This pairing represents the two sides of motherhood where love and care are present, but “it is suffocating and it’s aggressive or violent sometimes.” It’s this second aspect that is typically excluded from our classical narrative of motherhood or family, Partegàs pointed out. Typically, the family is depicted as a “pure, beautiful space of harmony,” she said.

“It’s not like that,” she added, laughing, “And everyone who has a family probably knows that.”

Because her work has included more and more of her experience as a mother over the past six years, this latest iteration of the basket series feels like a natural progression to Partegàs. She’s been immersing herself in books that consider the contradictions in motherhood as well, including “A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother” by Rachel Cusk and “Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty.”

Photo by Ester Partegàs

Emma McAleavy was Listings Project's Content Editor. During her tenure at Listings Project she brought the stories of our community to life on our blog and in our monthly newsletter. Emma’s writing has also appeared in The New York Times, Outside Magazine, and Architectural Digest.